It was to have been an idyllic cruise

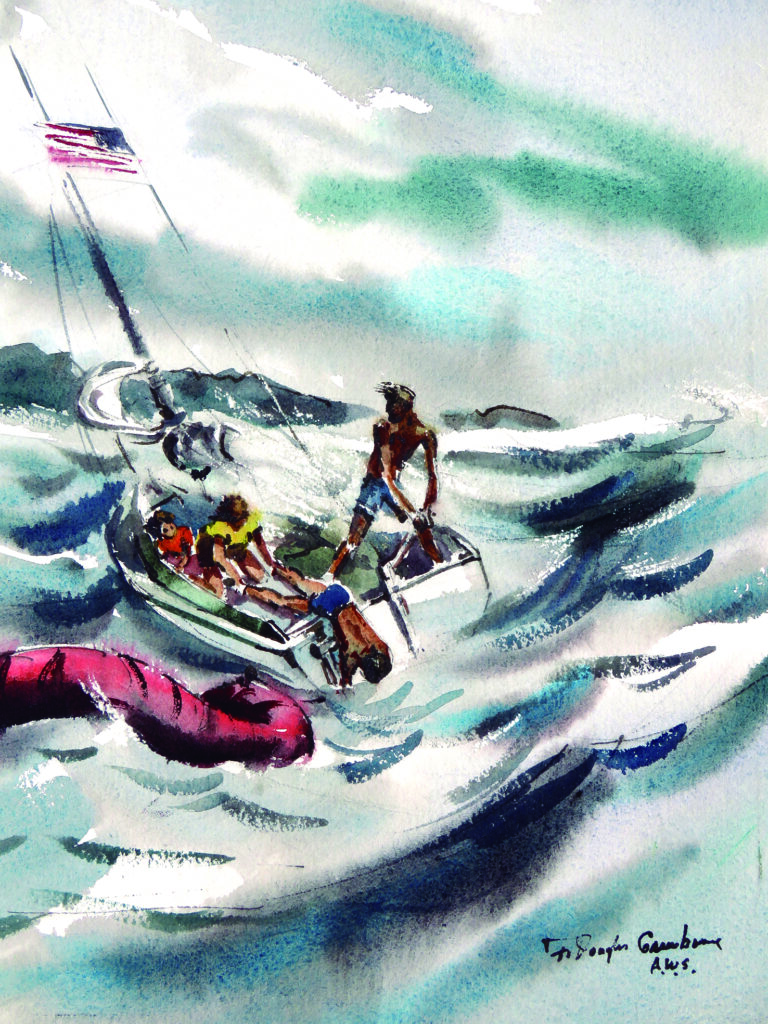

The sailboat was acting crazy. With the bow high in the air, it leaped from the water. It shuddered and tilted to the right and plunged. Water rushed from its sides as it cut a wave. All at once the boat was being swept from the cove into the boiling Gulf of California by a wind that had hit like lightning.

Holding on to the boom, I struggled to my feet. The low rise of land before us rushed past the bow. What had happened to the anchors? Did the ropes break or did the anchors pull loose from the bottom? Maybe the anchor post was pulled out.

The boat was broadside to the wave now. I thought we’d capsize if I didn’t get control fast.

I had taken numerous turns of rope around the handle so the tiller wouldn’t swing in the waves. I rushed to free the tiller. The next wave could swamp the boat or turn it over. When the last loop was off, I pushed the tiller hard to starboard to bring the stern into the wind. But the boat continued the same way. We were even with the end of the point. I shouted, “I can’t turn it around, I can’t turn it. Lane, get the motor started quick!”

My 18-year-old son leaned over the end of the boat and wrapped the starter rope.

“Did you choke it?”

“Yes,” he said.

“Did you open the gas?”

“Yes.”

Lane pulled the rope. It didn’t start. He rewound the rope and pulled again. It started.

I worked the tiller. Nothing happened. I pushed it back and forth. Still nothing. “The anchors. Lane, the anchors up, I can’t turn the boat.” He rushed forward. I watched the waves coming at us. “Are the anchors up?” I called.

“One is. I’m pulling the other one up now.”

“Hurry, hurry, Lane.”

We had entered open water. The boat started to come around. The stern rose and the propeller whirled faster and at a higher pitch as it left the water. Then a wave washed the stern, and the motor was muffled.

“Dad, turn the boat.” Lane was beside me. “The rope will get into the motor,” he shouted.

The motor stopped abruptly. The six feet of chain that runs between the rope and the anchor was wrapped around the propeller. “Hold the tiller,” I said. I knelt to free it. I whipped my arm back in pain. I had burned my wrist on the exhaust pipe.

When the propeller was free, I shouted, “Get the anchor in and start the motor!” We were broadside to the waves again. Lane dumped the anchor into the cockpit and started the outboard engine. I swung the tiller to the side. The boat refused to turn. “Dammit, the rudder isn’t big enough. The boat should have a larger rudder.”

Suddenly something red was flashing before my eyes. Our raft, tied to the pulpit with a short piece of rope, was being flipped like a cartwheel. I yelled. My wife Phyllis ran to stop it from whirling.

The motor stopped again. The rope was tangled in the propeller. Lane peered into the water. “Get the rope off as fast as you can,” I told him.

Lane said, “I need a knife, I’ll have to cut it off. It must be wrapped around twelve times.”

I looked around and saw a knife. Phyllis had used it to clean fish. IT had a serrated blade like a saw.

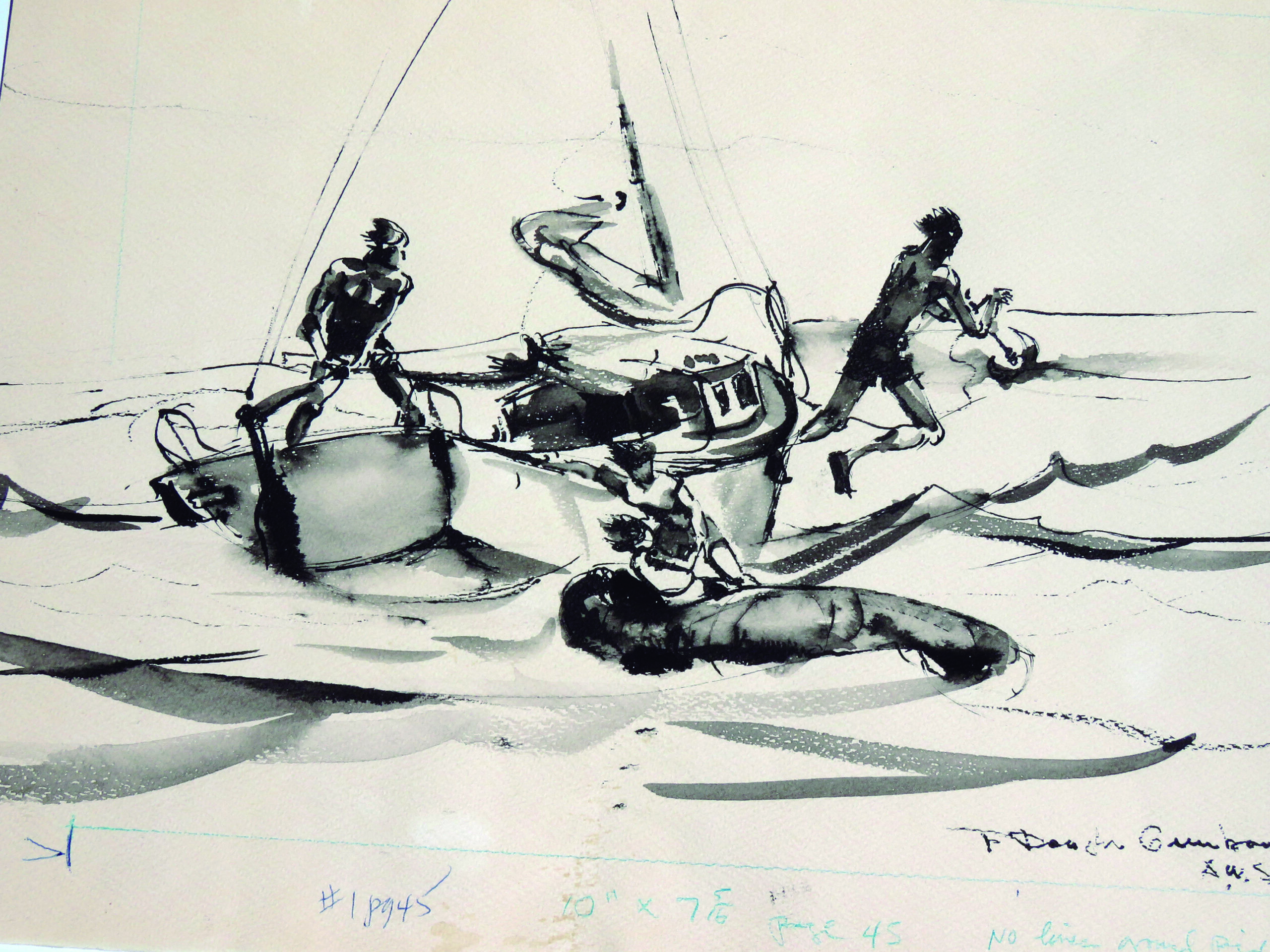

“Mom, hold my ankles,” Lane hollered as he spread flat on the deck. My wife’s arms and hands were wet, as were Lane’s legs and feet. I hoped she could keep a grip on him. Lane worked forward until he was far over the back of the boat. The boat dipped, then sprang up…Each time the stern went down, Lane disappeared to his waist in a wave.

I look forward. The shore got closer. We moved at a terrific speed. I wanted to hurry Lane. I wanted to tell him we’d be washed up on the rocks if he didn’t hurry.

We had vacationed in Mexico for fifteen years. Baja’s Pacific Coast kept drawing us back. Until three years ago we were content with exploring the same beaches and tide pools, with surf fishing clam digging and roaming familiar countryside. One afternoon I watched a sailboat glide south. I envied the captain. I thought it was the perfect way to further an intimate relationship with land and sea. To move with the wind, to land on a remote island. I had to have a sailboat.

Visits to marinas in California and literature collected during the next two years made my dram seem unreachable. Owing a sailboat with the size and fitting I wanted was beyond my reach. Building a boat seemed to be a way to cut expenses, but my desire could not wait that long.

A 22-foot sloop became my pacifier. Quite a comedown from my original aim, but the boat had sleeping facilities for four and a roomy cockpit. The most important feature was heavy lead ballast. For the oceans, a safety margin is desirable.

Now, I was thinking thank God for this sturdy vessel as I watched my 7-year-old daughter Lonnie, clinging to the cabin rail.

Lane was under water again. To myself I said, “Lane, for God’s sake hurry!”

“It’s off, the propeller’s free,” he said, as he wiggled back onto the deck.

I shouted my next order. “Phyllis, get the sea anchor. We’re moving too fast. We’re going into the rocks. No, wait. Lane, you get it. Phyllis, get the raft tied down to the side of the boat.”

Lane was back with the anchor. “Tie the rope to it,” I said. I pointed to a coil of rope hanging on the cabin. “As soon as it’s tied own throw it out behind us.”

The shore was much closer. The anchor sank below the water. I didn’t know what to expect. Lane fastened the rope to a clear. The rope tightened. The boat slowed as the anchor filled itself. The waves rushed past us. We had been moving with them, but the anchor had cut our speed by half. The boat turned stern to the waves, the way I wanted it to be.

Now the rudder was responding to my wishes. We were still sliding too fast across the milky grey-green water. The rocks were close. I thought we wouldn’t make it, that my boat would be smashed to pieces.

I looked for Lonnie. She had her lifejacket on. “Get your life vests on,” I ordered. I wondered how we’d go in the water. The rocks would be murder. When the boat was about to hit, I’d grab Lonnie and jump.

“Gene, look, the estuary. The water is calm in there. Head the boat into the estuary,” Phyllis shouted. Estero Tastiota was shown on our chart, but we had decided it offered no sanctuary because it was just a tidal flat. Deep or not, it was our only hope. I moved the tiller. It did not good.

“Try to go in at the end of the rocks, Dad. That looks like the entrance,” Lane yelled. I pushed the tiller again. “The sea anchor wouldn’t let me turn. Get the anchor up.” Lane grabbed the rope.

“I can’t get it in, it’s too heavy.”

“The spill rope, we forgot to put the spill rope on it.”

Lane was using every ounce of strength as he heaved at the rope. “Get the gaff,” I yelled at my wife. “Try to spill the water when it gets close.” The anchor popped above the water. Two more long pulls and it came out. Water poured from its funnel shape.

We missed the opening. The boat headed for a sandy beach. I thought that was better than rocks. The boat stared to turn its side to the waves.

“Phyllis, get the raft. You and Lonnie get off the boat, get to shore. Lane, hold the tiller.” I locked up the anchor which earlier had been tangled in the propeller and grabbed the rope. I heaved the anchor. Holding the rope right, I jumped. I touched bottom and my head was out of the water. I felt along the rope to find the anchor. I found the chain. Letting it slip through my hands until I touched the shaft of the anchor, I fumbled for a firm hold. Each time a wave hit the boat; the anchor was yanked forward.

“Lane, jump in with the other anchor,” I shouted. I saw Lonnie hanging on to Phyllis as they fell into the raft.

I yelled to Lane, “Take the anchor that way, in a vee shape from the bow, try to dig it into the sand with the flukes down, then stand on it.” I pushed my anchor into the sandy bottom. It came out as another wave hit the boat. The anchor shot ahead, dragging me with it. Lane was having the same problem.

All at once it started to rain. Lane was almost blotted out by the sudden downpour. The boat was barely visible. Stay with it, Lane.” My teeth chattered as I fought to keep my place on the plowing anchor. Incredibly, the rain slammed down with even greater force. I had read somewhere that tropical rain is so dense at times that people, and animals can suffocate from lack of air.

It seemed unreal that just a few days before we had set sail from San Carlos Marina at Guaymas. Our destination was a tiny spot on our chart, Isla San Pedro Martir. Our first night, twenty miles from San Carlos, we had anchored off the island San Pedro Nolasco. We all agreed our first encounter with the sea was all we had hoped. At night we sat and peered into the black water, fascinated by strange creatures glowing as they moved below. The island is home for hundreds of seals and birds. In darkness we could hear the more curious seals as they swam around the boat for a closed look. Their barking and squabbling continued through the night.

Early the next morning I set our course for Isla Martir. The wind was right, and the boat responded perfectly. As Nolasco became smaller to our stern, we became silent. The wind had increased steadily since our departure. The main and Genoa strained as we raced ahead. The drop keel hummed at a higher pitch. Clouds had appeared on the horizon in all directions. A huge bank of grey was spreading from Baja California. I had set a time limit for our sighting of San Pedro Martir. At 2 p.m., seven hours sailing from Nolasco, I altered our course to take us to the closest shore, the mainland of Mexico.

Our estimated distance from the Sonora shore was twenty miles. The clouds continued the spread. The strong wind from the south widened the waves and built them into mountains and valleys. An hour before sunset we eased into a small cove where the water was fairly calm, but the land offered little protection from the wind. For two days we had remained at anchor, waiting for the weather to settle.

The rain eased and finally stopped. Lane and I left the anchors which seemed to be holding now and we made our way to the boat. Each wave sent the bow high into the air. We could feel the vibrations under our feet as the lead keep smashed the bottom.

She had missed the rocks only to end up pounding out her guts on the beach. We circled the boat. At the stern we found the first obvious damage. The motor and rudder were wrenched violently as the boat trashed. When the boat plummeted down, both were smashed into the bottom. Two metal brackets were holding the motor. One was broken in half, the other twisted. The lower half of the rudder looked as if it were about to fall away. A jagged crack showed clearly.

Phyllis and Lonnie walked to a house near the estuary. They returned with a Mexican couple, Carmen and Eduardo Corral. I apologized for our unexpected visit. “This is our first experience with your famous Chubascos.”

“No, no, it was not a Chubasco, it was a cyclone.” In the fifteen years they had lived here they had never witnessed such a storm. I asked Eduardo if he could round up enough men to free the boat from the beach and bring it into the estuary. He said there were no other people for miles and the roads were impassable because of the torrential rains. I resigned myself to the loss of my boat. I thought it would be battered to pieces by morning.

We spend the night on a sand dune. The next morning, I was astonished to find the boat had survived. I removed the rudder to make a temporary repair. It was a good thing, because early in the afternoon the nine men came down the beach. Somehow Eduardo had come up with help. After two hours, the boat was inside the estuary.

At low tide the boat heeled and laid on its side as the water flowed from the estuary, exposing a bent drop keel.

In a few days we faced still another problem, The food and water situation became critical. Plenty of both had been stowed for the time expected at sea. When our water ran out, Carmen supplied us with rainwater collected during the storm. Cut off from their source, which was miles away, they relied on the same water.

When our food ran out, clams became our main diet. They were plentiful and easy to get in the estuary.

It took a week to make the necessary repairs for our trip back to Guaymas. The return would have to be made without the drop keel. Removing the keel was the greatest problem. Working each day at low tide, with the boat on its side in murky water, we finally released the keel from the hull.

Ten days after the storm beached us, we rode the ebbing tide back into the gulf. With the wind now from the north, the main sail and Genoa filled as we began the 35 miles back to Guaymas.

In less than an hour, the sea picked up. The boat heeled to its side as the wind increased.

There was no hum from the drop keep now, but the boat seemed all right without it. I kept the bow on Punta Blanca, a white rock cliff halfway to Guaymas.

The waves had risen considerably when we entered a small cove near the point. Phyllis and Lane had suggested sailing all the way, but I felt it wouldn’t be safe in the dark.

We had to settle for this indent with a large rock monolith we hoped would block the wind. Lane looked for obstructions. Wind whipped the said as Lane prepared to drop anchor. “We can’t anchor here.” I said I pushed the tiller to leave the windswept cove. The white cliffs of Punta Blanca grew darker as we sailed south.

Lane filled the tank and started the motor. Both sails were lowered and tied and compass and running lights were lit for our run to San Carlos Marina. Heading to deep water and a safer distance from shore, I set a course by the compass.

Sky and water became one as the last hint of light faded. I guided the boat through water that grew rougher by the minute. My right arm and shoulder ached from hours of straining. Luckily, I sighted a star near the mast to help me keep my course. The battery ran down, leaving us without running or compass lights. A fait image of whitecaps helped guide the boat through the waves.

At 11:30, five and half hours from Punta Blanca, we entered the outer bay of San Carlos. The rock cliffs showed from the glow of city lights, but on the water all was black. The anchors dropped for our last night’s stay on the Sea of Cortez. Dawn showed us the entrance, less than 50 yards from our bow.

Permission for reprint given by Lane Frank

Originally published in 1972