Don Miguel Hidalgo y Costilla was born May 8th 1753, to a well-respected Criollo family (pure-Spanish, born in the Americas). As a child he learned the languages of the Indios. In 1759 some privileges and opportunities, previously withheld from Criollos, were granted for the first time since the Conquest; Criollos were finally allowed admission to universities. Hidalgo studied Theology and the liberal arts, including Italian and French. He was ordained as a priest in 1778, however, he did not live the expected lifestyle of an 18th-century priest. His studies of the Enlightenment-era ideas lead him to challenge the political and religious norms. He did not believe in celibacy for priests or the absolute authorities of the Pope and the Spanish king. In his lifetime he lived with 2 different women and fathered 5 children.

Don Miguel Hidalgo y Costilla was born May 8th 1753, to a well-respected Criollo family (pure-Spanish, born in the Americas). As a child he learned the languages of the Indios. In 1759 some privileges and opportunities, previously withheld from Criollos, were granted for the first time since the Conquest; Criollos were finally allowed admission to universities. Hidalgo studied Theology and the liberal arts, including Italian and French. He was ordained as a priest in 1778, however, he did not live the expected lifestyle of an 18th-century priest. His studies of the Enlightenment-era ideas lead him to challenge the political and religious norms. He did not believe in celibacy for priests or the absolute authorities of the Pope and the Spanish king. In his lifetime he lived with 2 different women and fathered 5 children.

Because of his unconventional progressive ideas, he was eventually assigned to be the parish priest in Dolores, Guanajuato; when he arrived he was appalled at the poverty of the community. He used his extensive education to promote grape cultivation, raising silkworms, beekeeping and the making of bricks and pottery in order to help the poor develop economic improvements in their lives. His goal was to make the Indians and Mestizos more self-reliant and less dependent on Spanish economic dictates. However, these activities violated policies that were designed to protect the income of the European Spaniards’ agricultural and industrial profits; Hidalgo was ordered to stop these activities.

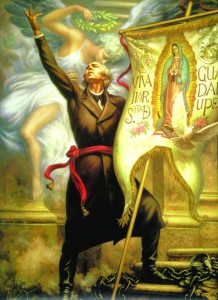

On the night of September 15th 1810 he ordered armed men to force the release of inmates from the prison. On the morning of the 16th Hidalgo rang the church bell calling Mass, which was attended by about 300 people, including hacienda owners, local politicians and Spaniards. There he gave what is now known as the Grito de Dolores (the Shout or Cry of Dolores), calling the people of his parish to leave their homes and join with him in a rebellion against the current government of New Spain, in the name of their King.

On 28th of September 1810, Hidalgo arrived at the City of Guanajuato with rebels; the majority of which were armed only with sticks, stones and machetes. The town’s Spanish and Criollo populations took refuge in the heavily-fortified granary. The insurgents overwhelmed the defenses after two days; everyone inside was killed, an estimated 400 – 600 men, women and children.

On the 17th of October 1810 Hidalgo issued proclamations against the Peninsular (European Spaniards) whom he accused of arrogance and despotism, as well as enslaving those in the Americas for almost 300 years.

Hidalgo argued that the objective of the war was “to send the Peninsular back to the motherland because their greed and tyranny lead to the physical and spiritual degradation of the Mexicans.” On December 6th 1810, Hidalgo issued a decree abolishing slavery, for the first time in the Americas; threatening those who did not comply, with the penalty of death. He abolished tribute payments paid by the Indians to their Criollo and Peninsular lords. He ordered the publication of a newspaper called Despertador Americano (American Wake-Up Call). He marched across Mexico and gathered an army of nearly 90,000 poor farmers and Mexican civilians, who attacked and killed both Peninsular and New World-born Spanish elites.

Hidalgo’s troops lacked training and were poorly armed. Many of these people were angry after so many years of hunger and oppression. Because of the lack of military discipline, the insurgents soon fell into robbing, looting and ransacking the towns they were capturing. Some of his supporters were adamantly opposed to Hidalgo’s encouragement of violence and outright rebellion.

He was betrayed and captured on the 21st of March 1811. Hidalgo was officially defrocked and excommunicated on the July 27th, 1811. Following his conviction of treason by a military court, he was executed in front of a firing squad on July 30th 1811 at 7:00AM. His body, along with 3 other insurgents, was decapitated. Their heads were put on display at the four corners of the Alhóndiga de Granaditas in Guanajuato and remained there for ten years, until the end of the Mexican War of Independence, to serve as a warning. Hidalgo’s headless body was first displayed outside the prison but then was buried in the Church of St. Francis in Chihuahua. In 1824 his remains were transferred to Mexico City.